It is 7.15am on a sunny Wednesday in Blantyre and Jumbe Township is brimming with logs falling from massive heaps of firewood. The pieces of wood sliding into Limbe-Machinjiri Road block traffic during rush hour. However,

the traffic jam is made worse by two trucks offloading firewood at the commercial city’s fastestgrowing

firewood market. This personifies the city ’s increasing appetite for firewood mostly used by rural populations. As the boys atop the trucks throw logs onto the heaps on the roadside, people rushing to work kick the logs out of way and women bend to pick their preferred pieces for domestic use.

Every morning, the women f r o m Ma k h e t a , Mk w e p u , Madulira, Nakulenga, Mkwate, Khama, Nkolokoti and the rest of Machinjiri and surrounding townships flock to Jumbe to buy firewood for domestic and commercial use. Some of them live in homes with electricity, but say they cannot afford using it for cooking. Others are prohibited by their landlords, so they just use electricity for lighting only.

Atupele Chitsulo, from Madulira, 27, says she buys a K800 bundle daily. “With this, I will heat water for family tomorrow morning, cook breakfast, lunch and supper,” she says, tying the firewood together. Chitsulo finds firewood more affordable than charcoal, which is getting scarce. The country imports some charcoal from Mozambique.

“In a day, I use four packets of charcoal worth K300 each. I save K400 using firewood,” says the mother of three. Chitsulo would be spending K36 000 a month on charcoal. A person earning the minimum wage—K25 000—would need an extra K9 000 to meet this cooking energy bill, but she saves K12 000 per month on firewood.

This partly explains why the rush for firewood in urban setting once high on charcoal. The Department of Energy reports that nearly half of urban dwellers cook on charcoal fire. The main consumers include traders vendors selling chips and other fast food by the roadside as well as households without electricity and low-income earners. “Charcoal is the new gold.

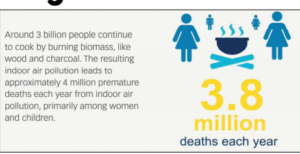

The prices are sky-rocketing and some of us cannot afford it anymore. At Madulira charcoal market in Machinjiri Township, a 50-kilogramme bag costs an average of K9 000. That’s why I prefer firewood,” says Alice Mbana, from Jumbe. However, some landlords forbid tenants from using firewood to reduce in-door air pollution caused by smoke and soot. But low-income earners have little choice, with 97 percent of the country’s population using firewood and charcoal for cooking.

As a result, the Forestry Department estimates that up to three in every 100 trees go up in smoke every year. The worst deforestation rate in southern Africa brings to light the country’s energy poverty as only 11 percent of Malawi’s population has electricity. However, only one percent of the haves uses it for cooking. Many bemoan high tariffs even though some donors wish the pricing was higher.

As trees burn in kitchens, traders travel longer and spending more to fetch firewood for sale. Many travel at night to dodge police checkpoints. Watching boys offloading firewood at Jumbe, Ajibu Kamwana said: “Neighbouring forests have disappeared since I joined this trade five years ago. I used to get firewood from Machinga forests.

Nowadays, I travel further to Mtukusi Hills to buy wood.” The depletion of trees neighbouring hills and forests means higher expenditure on transportation. “I pay K180 000 to transport a truckload to Blantyre,” he says. Kamwana earns K800 000 after selling his firewood, enough money to supports his family.

“I have nine children and I pay school fees for four of them using the proceeds of this business,” he says. Emily Steward, sitting on the heap of firewood as she awaits customers, ventured into the business in 2003.

“At that time, there were plentyof trees and we didn’t have to travel long to source firewood. Now, we spend weeks to fill a truck. We procure it from as far as Chikwawa,” she says. Due to rising demand for wood in the city, a truckload is sold out within three days. “Jumbe Market receives two trucks carrying about 10 tonnes each. Within days, the firewood is gone,” says market chairperson Langford Saidi.

Those who witnessed the market’s humble beginnings in the 1990s say the sales have never been higher. The 36-hour blackouts in 2017 partly made Jumbe the preferred destination for both buyers and traders. “At first, traders were selling pinewood from Zomba, but pine has become scarce since the country’s second-tallest mountain lost its plantations to loggers. So, we are turning to indigenous firewood,” says Saidi.

Sandikonda Piyo endures some hide-and-seek while hauling firewood and charcoal into the city. “I charge K120 000 to transport wood from Nanchidwa Forest in Mulanje Mountain to the bottom. From the foot of the tallest mountain to Blantyre, I charge K150 000,” he says.

Before living Mulanje, Piyo shells K20 000 to get permits from the Forestry Department in Mulanje. He also pays K30 000 on the weighbridge and K8 000 to buy his way past four police roadblocks on the Robert Mugabe

Highway. “At Jumbe, I pay K10 000 to the boys offloading the logs and another K10 000 to the owner of the place where I put the wood,” he says.

And log by log, the roadside trading centre is getting bigger, with every undeveloped space dotted with heaps of firewood. The oddity bares the city’s thirst for modern energy that saves trees, lives and the planet.

Source: The Nation_Sunday, August 18, 2019- by Ayami Mkwanda-Staff Writer